In recent posts, I’ve described some factors that guide tech adoption. My perspective of adoption behavior is informed by research, my personal habits, and my observations of others’ habits. The research implicates personal (personality) factors guiding adoption behavior – and success. This isn’t a radical view and really sounds like common sense. Who we are; what we do for a living, our interests and passions, friends, goals and upbringing shape our values and reflect what we adopt. Added together, these factors appear to form an adoption profile. I’m going to call my approach a “technology personality inventory”.

“individuals construct unique yet malleable perceptions of technology that influence their adoption decisions.” (Understanding Technology Adoption: Theory and Future Directions for Informal Learning – Straub – 2011)

Considered together, multiple models of behavior change provide helpful clues to adoption habits. My goal is to create a model that is practical, in that it helps me understand a person’s adoption habits in action. In casual conversations, classes, and 1:1 consultation, I have opportunities to hear how people view their technology. I primarily talk with family (of all ages), students from 40-84, and colleagues who work in technology. The conversation usually includes these questions:

- what they are using?

- what they use it for?

- how well they understand it?

- what is their skill level?

- how much they enjoy or dislike the tool?

- what do they feel/think they need to know to improve?

- other tools they have considered for this and other tasks?

While my interviews are not formally structured, I have developed a habit of asking and listening to answers to these questions. My approach comes fairly natural. As a behavior consultant, I assessed the behavior of children based on their emotional / cognitive understanding of people and the environment. An important part of my behavior analysis was understanding the motivation of my students. Operating on the assumption that all behavior is goal oriented, I listened closely to students explanation of what they like and what they avoid. I listened to teachers describe behavior incidents; what occurred before, during and after the event. As I develop a model for understanding adoption behavior, I believe that I can refine my inquiries and the insights revealed. As I apply my behavior analysis skills to my work in technology, the following theories (presented in chronology to their development) seem helpful:

Theory of reasoned action – (TRA) Developed by Martin Fishbein and Icek Ajzen (1975, 1980). Model for the prediction of behavioral intention, spanning predictions of attitude and predictions of behavior. The theory was “born largely out of frustration with traditional attitude–behavior research, much of which found weak correlations between attitude measures and performance of volitional behaviors” (Hale, Householder & Greene, 2002, p. 259).

TPB is an extension of the TRA and includes an additional construct, perceived control over performance of the behavior. TRA and TPB both assume the best predictor of a behavior is behavioral intention, which in turn is determined by attitude towards the behavior and social normative perceptions regarding it.

I agree that intention is a key to understanding the direction of choice. Understanding a person’s intention, their hopes and fears (social, technical, economic, access) says much about where they are headed. Intention is a broad concept and represents many forces. Clearly, humans exchange intentions and model evidence of our choices to one another. This creates a sort of feedback loop of adoption that shapes the diffusion of innovation. This phenomena has been revealed in recent descriptions of mirror neurons. This is a very hot topic within the field of neuroscience. Mirror neurons are ignited in our bodies/brain when we observe someone performing a behavior or using a tool. This was first uncovered in the 1990s in monkeys.

The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) is an information systems theory that models how users come to accept and use a technology. The model suggests that when users are presented with a new technology, a number of factors influence their decision about how and when they will use it, notably:

Perceived usefulness (PU) – This was defined by Fred Davis as “the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would enhance his or her job performance”.

Perceived ease-of-use (PEOU) – Davis defined this as “the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would be free from effort” (Davis 1989).

TAM replaces many of TRA’s attitude measures with the two technology acceptance measures— ease of use, and usefulness. TAM has been revised (TAM2 and TAM3). Ease of use and usefulness stand out as helpful concepts to consider in

The Matching Person & Technology Model (MPT) was developed by Marcia J. Scherer, Ph.D. beginning in 1986. It organizes influences on the successful use of a variety of technologies: assistive technology, educational technology, and those used in the workplace, school, home; for healthcare, for mobility and performing daily activities. Specialized devices for hearing loss, speech, eyesight and cognition as well as general or everyday technologies are also included. Research shows that although a technology may appear perfect for a given need, it may be used inappropriately or even go unused when critical personality preferences, psychosocial characteristics or needed environmental support are not considered. The Matching Person and Technology Model is operationalized by a series of reliable and valid measures that provide a person-centered and individualized approach to matching individuals with the most appropriate technologies for their use.

While it has been primarily applied to special populations in need of assistive technology, it describes factors that apply to any person. Let’s face it, we all have our quirks, abilities and “disabilities”. Our abilities differ by degree and are more pronounced in different situations and different technology. Steven Hawking may have physical limits but he is adept with the technology he has adopted.

When matching person and technology, you become an investigator, a detective. You find out what the different alternatives are within the constraints. —From Living in the State of Stuck: How Technology Impacts the Lives of People with Disabilities

This describes my role as behavior consultant. I applied my detective skills (playing Sherlock Holmes) with my students, trying to uncover their triggers and motivations. My focus was in helping the student to adapt to the demands around her. Needless to say, the ideas within the MPT model are very familiar to me. Instinctively, I pay attention to learning styles, abilities, receptive and expressive communication modes.

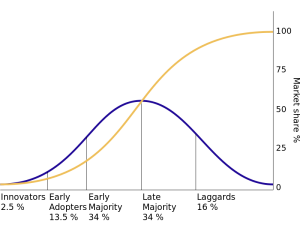

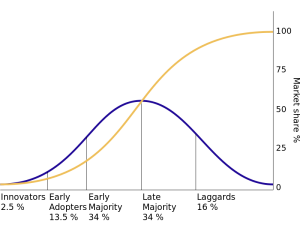

As important as it is to understand the personal stories of people adopting technology, it is equally important to consider adoption from a more general theory. Specifically, it’s helpful to consider the macroscopic, social arc of adoption. The Diffusion of Innovations theory is just such a perspective. Often referenced in conversation about technology adoption and marketing. Central to diffusion is communication and the rate at which an innovation moves into the general population. The saturation of an innovation has influence over it’s adoption. As saturation increases, it creates feedback to people at all stages of adoption; Innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority and laggards.

Diffusion of Innovations is a theory that seeks to explain how, why, and at what rate new ideas and technology spread through cultures. Everett Rogers, a professor of communication studies, popularized the theory in his book Diffusion of Innovations; the book was first published in 1962, and is now in its fifth edition (2003).[1] The concept of diffusion was first studied by the French sociologist Gabriel Tarde in late 19th century[2] and by German and Austrian anthropologists such as Friedrich Ratzel and Leo Frobenius.[3]

Roger’s work asserts that 4 main elements influence the spread of a new idea: the innovation, communication channels, time, and a social system. With the advent of social networks, the vectors for innovation have increased dramatically. Social media adoption has become a enabler to technology adoption in general; wheels creating wheels.

I’m excited to apply these perspectives in my conversations with my students, family and random people I meet. It will be interesting to see the patterns in these technology personality inventories. I intend to share my findings along the way. Stay tuned!

That grey box that you see connected to the computer is now the brains of the computer. Using the hard drive delivered from the US and some random flash drives that I brought with me, I spent the week diagnosing and fashioning a system that works. It is pretty or convenient but it works.

That grey box that you see connected to the computer is now the brains of the computer. Using the hard drive delivered from the US and some random flash drives that I brought with me, I spent the week diagnosing and fashioning a system that works. It is pretty or convenient but it works.